Category: Contributor’s corner

The concussion puzzle: is there a risk profile for sport-related concussion?

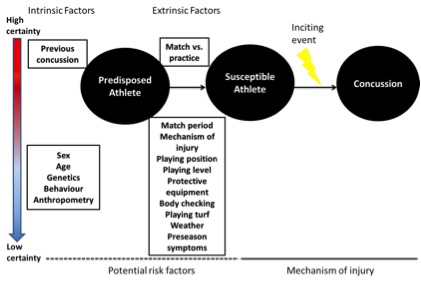

Figure 1: A proposed model summary of the systematic review of literature and adapted from Meeuwisse’s athletic injury aetiology model [7].

Figure 1: A proposed model summary of the systematic review of literature and adapted from Meeuwisse’s athletic injury aetiology model [7].

From all previous risk factors identified for sports concussion, only a previous concussion(s) and playing a match compared to practice has strong scientific evidence.

Concussion is caused by a force transmitted to the head resulting in symptoms ranging from a severe headache to loss of consciousness and is one of the more severe sports injuries with professional club rugby players missing up on average 12 days during two seasons [1,2]. A reported compensation pay-out of over $700 million by the American National Football League (NFL) to over 4500 former NFL players or their relatives for severe and debilitating complications, they claim resulted from concussions sustained whilst playing NFL [3,4]. This widely publicised court case has raised concern over concussion injuries not only in athletes and their families across sports [5], but also sporting organisations such as the International Rugby Board (IRB), which has implemented a controversial side-line concussion test for suspected concussions [6].

However, sport related concussion still remains a hotly debated injury mainly due to the lack of understanding of the aetiology and the individual variations in symptom presentation, which makes diagnosing and managing concussions challenging. In light of this, our research team undertook a comprehensive systematic review of the scientific literature on concussion risks that was recently published online (http://bjsm.bmj.com/cgi/content/full/bjsports-2013-092734). After a critical search and evaluation of over 13 000 articles, we identified 86 scientific research articles investigating possible risks for concussion in sport with the main findings summarised below:

- Athletes who have experienced a previous concussion(s) and playing a match compared to practice were the only concussion risks supported by strong scientific evidence.

- Although experts often state children and women are vulnerable groups[8], gender and age were amongst several potential risk factors for concussion which require further robust studies to confirm risk effect.

Although there is an abundance of papers on concussion in the scientific literature, there is still a need for robust research, preferably follow-up studies with sufficient sample sizes, to confirm concussion risks.

We suggest that there are inter-individual differences in the aetiology and manifestation of concussion and as such we are conducting a research study to investigate the genetic and non-genetic role underlying concussion risk and recovery. The future goal of this study is to further understand concussion in order to provide a model for individual diagnosis and therapy strategies improving concussion management especially in vulnerable groups such as youth players. To this end, we are in the process of inviting the top rugby-playing schools in South Africa and thus far extend our gratitude to Wynberg Boys’, Paarl Boys’, Paarl Gimnasium, SACS and Boland Landbou high schools who have eagerly accepted our invite to participate in our research study. We are equally excited to embark on this venture with them, as well as other top rugby playing high schools, to investigate why the incidence of concussion is so high our youth rugby players.

References:

- McCrory P, Meeuwisse WH, Aubry M, et al. Consensus statement on concussion in sport: the 4th International Conference on Concussion in Sport held in Zurich, November 2012. Br J Sport Med 2013;47:250–8

- Brooks JHM, Fuller CW, Kemp SPT, et al. Epidemiology of injuries in English professional rugby union: part 1 match injuries. Br J Sport Med 2005;39:757–66.

- Boren C: NFL, ex-players reach settlement over concussion lawsuits. The Washington Post online, August 29, 2013. Available at http://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/early-lead/wp/2013/08/29/nfl-former-players-to-settle-concussion-lawsuits-judge-says/ (accessed on 25 September 2013)

- Crepeau R: The NFL Concussion Settlement. The Huffington Post blog online, September 04, 2013. Available at http://www.huffingtonpost.com/richard-crepeau/nfl-concussion-settlement_1_b_3853120.html (accessed on 27 September 2013)

- Peters S: Moody: We used to treat concussion as a joke… now I worry about dementia. The Daily Mail online, September 22, 2013. Available at: http://www.dailymail.co.uk/sport/rugbyunion/article-2428431/Lewis-Moody-We-used-treat-concussion-joke–I-worry-dementia.html (Accessed on 29 September 2013)

- Guyer J: IRB to review sideline concussion test. The Wide World of Sports online, July 18, 2013. Available at http://wwos.ninemsn.com.au/article.aspx?id=8691586 (accessed 20 September 2013)

- Meeuwisse W. Assessing causation in sport injury: A multifactorial model. Clin J Sport Med. 1994;4:66–170

- Kutcher JS, Eckner JT. At-risk populations in sports-related concussion. Current sports medicine reports 2010;9:16–20

About the Authors:

Shameemah Abrahams majored in Biochemistry and Physiology for her undergraduate BSc (2008 – 2010) with honours in Physiology, specialising in Neuroscience, (2011) at the University of Cape Town (UCT). She is currently (2012-) in her second year as a MSc (Med) student at the UCT/MRC Exercise Science and Sports Medicine research unit, UCT. Her MSc project deals with both the identification of genetic and non-genetic predisposing factors of concussion risk in South African rugby players. Her research interests include brain injury, physiological changes during exercise and genetic predisposition to injury.

Sarah Mc Fie completed a BSc in Chemical, Molecular and Cell Biology, majoring in Genetics and Human Biology, in 2010 and an Honours specializing in Neuroscience in 2011 from the University of Cape Town. She started her current degree, an MSc in Exercise Science, at the Exercise Science and Sports Medicine research unit, UCT, in 2012. Her MSc research project aims to identify intrinsic and extrinsic risk factors for risk and severity of sport-related concussions. Her research interests include genetics, neuroscience and sport.

“You can’t manage what you don’t measure.” Monitoring training load and recovery in team sports

by Ben Capostagno and Wayne Lombard

In a recent editorial for the International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance, Iñigo Mujika highlighted the importance of quantifying training load.(3) If an athlete shows positive adaptation to training, it is important for the strength and conditioning coach to know the exact training load the athlete was exposed to. Likewise if the athlete shows a maladaptation to training, accurately collected training load data will indicate whether the training load was excessive or insufficient. One of the simplest ways to quantify training load is to multiply the duration of the session in minutes by a rating of perceived exertion for the session. For example, if a training session lasts 60 minutes and the athlete rates the session as 5 out of 10 for intensity, the training load should be 300 units.

Once the training load has been accurately quantified it is crucial to monitor how the athletes are responding to the imposed load. Daily monitoring has become more popular within sports science as athletes are constantly exposed to ever increasing training loads. The daily monitoring commonly takes the form of questionnaires and should include a subjective rating of fatigue. In addition, Kenta and Hassmen (2) identified four key areas of recovery that should also be monitored;

- nutrition and hydration

- sleep and rest

- relaxation and emotional support

- stretching and active rest

If the athlete is actively engaging in these four areas of recovery, but still reporting high levels of fatigue, then the planned training load should be adjusted accordingly.

It is important to partner the subjective measures of recovery with an objective measure. The most common target of objective measures is the autonomic nervous system. The autonomic nervous system is connected to a wide variety of systems within the human body and thus makes it a suitable target to monitor the overall well-being of the athlete.(1) Non-invasive measures of the autonomic system’s status include heart rate variability (HRV) and heart rate recovery (HRR). HRV appears to be gaining momentum as the objective measure of choice within teams and individual athletes. However, there is currently no clear consensus on the measurement and interpretation of HRR and HRV and therefore should be used with caution.

In conclusion there are simple, validated measures of both training load and the athlete’s responses to these training loads. Coaches and strength and conditioning experts are encouraged to use these or similar methods in order to manage their players during a competitive season.

Reference

1. Borresen J and Lambert MI. Autonomic Control of Heart Rate during and after Exercise : Measurements and Implications for Monitoring Training Status. Sports Medicine 38: 633-646, 2008.

2. Kentta G and Hassmen P. Overtraining and recovery. A conceptual model. Sports Medicine 26: 1-16, 1998.

3. Mujika, I. The Alphabet of Sport Science Research Starts With Q. International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance 8: 465-466, 2013.

About the Authors

Benoit Capostagno completed his BSc degree (cum laude) specialising in the Sport Sciences at the University of Stellenbosch in 2006. He continued his studies at the University of Cape Town’s Research Unit for Exercise Science and Sports Medicine completing his honours with a first class pass in 2007. He is continuing his postgraduate work with his PhD at this same unit and is investigating training adaptation and fatigue in cyclists. He has been a consultant with the Sports Science Institute of South Africa’s High Performance Centre’s Cycling Division since 2009. In addition, Ben has also assisted the Springbok Sevens Rugby team with monitoring the training status and levels of fatigue in their players since the 2008/2009 IRB World Sevens Series. Follow Ben on twitter @BCapostagno

Wayne Lombard completed his undergraduate and honors degrees at the University of Kwa-Zulu Natal (Durban). He then joined the Sports Science Institute of South Africa as a Biokineticist and Performance enhancement specialist at the High Performance Centre. He then went on to complete is Master’s degree and is currently registered for a PhD in exercises science at the University of Cape Town, focusing on athlete monitoring of training loads, recovery and fatigue. Wayne has worked with various of South Africa’s top athletes in all sporting codes, including some of South Africa’s Paralympic and Olympic athletes. Follow Wayne on twitter @waynelombard. You can also visit the Sport Science Institute of South Africa Website at http://www.ssisa.com/pages/high-performance/-high-performance-services.

The Visual Skills that shape every rugby players performance: Part 1

This article is by Grant van Velden (@gvanvelden) who is a Sports Vision and Decision Making Specialist working out of the Centre for Human Performance Sciences at Stellenbosch University. He has worked with Australian rugby stars James O’Connor and Quade Cooper, Springbok’s Juan de Jongh, Gio Aplon, Elton Jantjies, Morne Steyn & Pat Lambie,, the Springbok Sevens team, the Maties Referees Academy, Varsity Cup and Young Guns teams, Alan Zondagh’s Rugby Performance Centre (RPC), as well as South African kicking guru’s Braam van Straaten, Louis Koen and Vlok Cilliers. He is also the technical spokesperson for Nike Vision South Africa.

With the Super 15 heading into a crucial part of the season, I thought that it was fitting to highlight some of the visual skills that the players in the top teams of the tournament would possess. This will be the beginning of a number of articles that highlight these visual skills.

Today’s article will look at the visual skills of Dynamic Visual Acuity (DVA) and Visual Alignment, two visual skills that any rugby player needs to master in order to perform successfully at the elite level.

Dynamic Visual Acuity, also known as kinetic visual acuity, refers to the athlete’s clarity of vision while the athlete is in movement or while the athlete is tracking a moving object – in rugby this would relate to how clearly and precisely the player can send visual information to the brain for interpretation so that the correct motor response can be initiated. The more clear and precise the visual information, the more accurate is the information that is sent to the brain and the faster the brain is able to process that information. So a lock forward with good DVA will be able to give clear and precise visual information to his brain regarding the flight of the ball from a kick off, so that his brain can interpret the information an initiate the correct timing of the jump in order to secure the ball for his team successfully. Eben Etzebeth, one of the top lock forwards in the world, would more than likely excel at DVA task. This visual skill would also be particularly beneficial for a fullback, such as Willie le Roux, who is tasked with successfully catching aerial bombs while under immense pressure from the opposition.

Dynamic Visual Acuity, also known as kinetic visual acuity, refers to the athlete’s clarity of vision while the athlete is in movement or while the athlete is tracking a moving object – in rugby this would relate to how clearly and precisely the player can send visual information to the brain for interpretation so that the correct motor response can be initiated. The more clear and precise the visual information, the more accurate is the information that is sent to the brain and the faster the brain is able to process that information. So a lock forward with good DVA will be able to give clear and precise visual information to his brain regarding the flight of the ball from a kick off, so that his brain can interpret the information an initiate the correct timing of the jump in order to secure the ball for his team successfully. Eben Etzebeth, one of the top lock forwards in the world, would more than likely excel at DVA task. This visual skill would also be particularly beneficial for a fullback, such as Willie le Roux, who is tasked with successfully catching aerial bombs while under immense pressure from the opposition.

Visual Alignment is the ability to accurately aim the two eyes at a target, whether stationary or moving. Most people’s eyes are slightly misaligned, which is normal. Some athletes with an eye condition (such as lazy eye, turned eye, or crossed eyes) will have a more serious eye alignment problem requiring a doctor’s intervention. Eye alignment affects the athlete’s perception of the position of the target, as well as the speed and the distance of the target. As a result, any misalignment can be responsible for errors in aiming, timing, as well as eye-hand or eye-foot coordination. In addition, misalignment of the eyes can cause the athlete to adopt a poor posture and technique in order to compensate for the visual problem. Morne Steyn is a prolific goal kicker and is currently one of the leading point scoreres in this years Super 15 – it would not surprise me to find that Morne has a very good visual alignment. Misalignment could be a huge hindrance if you are a flyhalf wanting to better your goal kicking performance for example, but you just cannot seem to improve beyond a certain point. If your eyes are misaligned, it could be affecting your kicking technique so much so that you are not consistently striking the ball correctly.

Remember, keep your body fit and your eyes fitter!!

The next article in this series will discuss how to train these visual skills….